Lunch Box Surprises

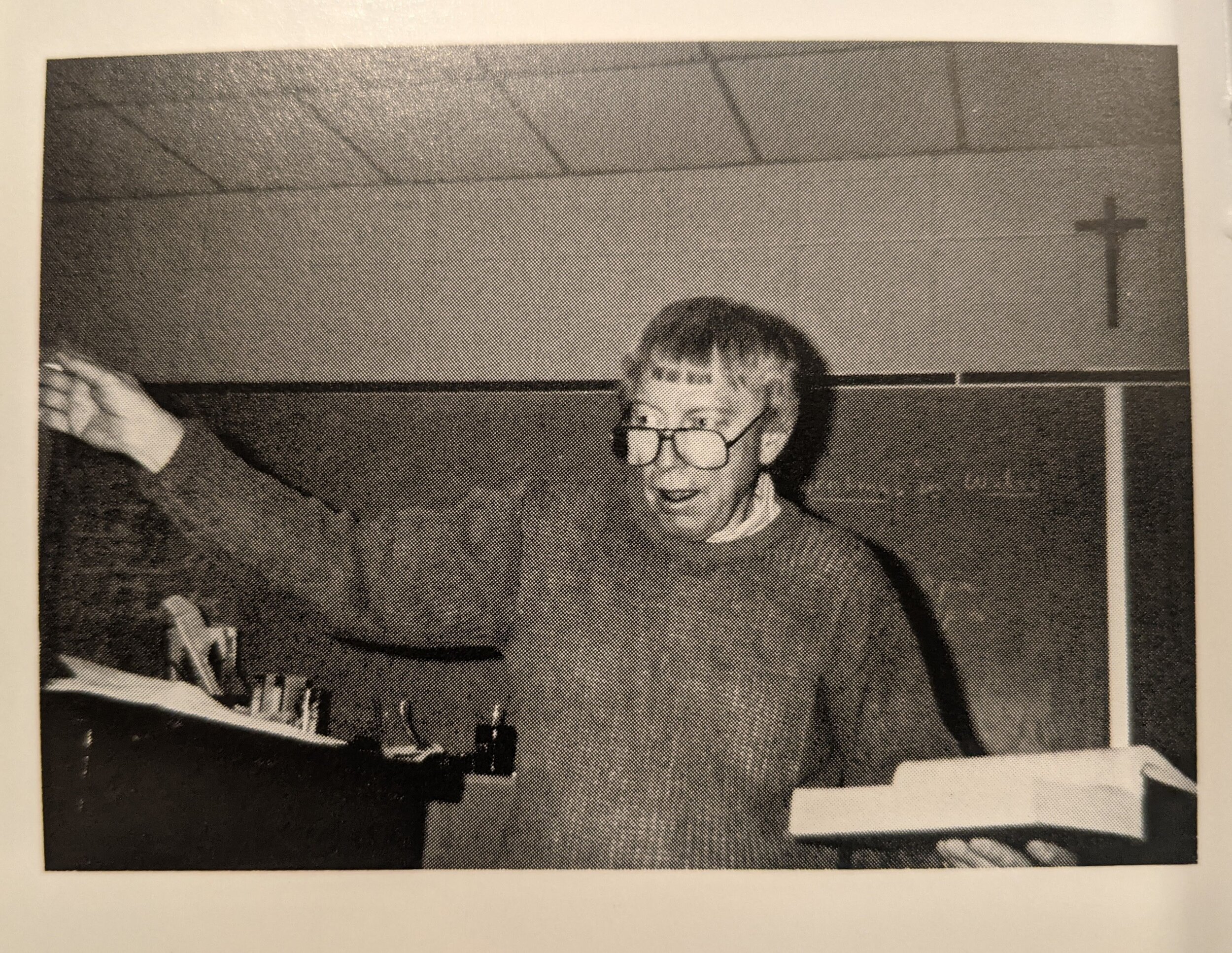

Malcolm Mosing (1924-2007)

I launched my writing career in the third grade. My first work was fictional, complete with a captivating setting, lively characters, colorful illustrations, and at least one major plot point. My mother carefully typed the story, a couple of sentences per illustrated page. My first published work. My first byline.

My second work was an adaptation called Twas the Night Before the Fun Fair written also as a third grader for the Holy Ghost[1] Grade School newsletter. In fourth grade, I wrote my longest piece yet—a chapter book entitled The Cougar, in which I experimented with formalism, beginning each chapter with “He woke up,” and ending it with, “He went to sleep.” In fifth grade, I did a lot of reading and didn’t produce much, but in sixth grade, I experienced a renaissance and produced several short stories in what I now refer to as my “Mystery Period,”[2] two of which were the beginning[3] of a series called The Bensen Brothers Mysteries. In eighth grade, I found my muse in lost love,[4] with my most noteworthy poem entitled “Almost Over You”[5] and my most noteworthy short story entitled, “Michael.”[6]

In high school, my career took a serious turn. I used the $400 I saved up from babysitting and bought an electric Smith Corona.[7] But more importantly, I got a writing mentor—my English teacher, Mr. Malcolm Mosing. He was an eccentric individual, passionate about literature, performance, and culture. Sometimes we’d skip Shakespeare altogether, and he’d just read us articles out of The New Yorker. He made us memorize “Jabberwocky” and “Buffalo Bill’s” and passages from MacBeth. He spent a lot of time staring out at us over the rims of his glasses as he chewed his gum with a long and deliberate diagonal motion of the jaw, his legs crossed and his elbow posed on podium, thumb rubbing against his fingers as he prepared to deliver a thought. I hung on his every word.

It was a prolific time for me. I would bring him my short stories, and he would give me his encouragement and advice. One day during lunch period as I stood next to him awaiting feedback on my latest masterpiece, he looked at me for a long while over the rims of those glasses and offered me this seminal piece of advice:

“Perhaps it’s time to consider writing about

something other than death.”

It’s true my recent line-up had included an old man who dies at sea, a boy whose twin brother drowns in a bathtub, and an unappreciated do-gooder who is turned to ash in a burning town hall. I’m sure the hot flush in my cheeks communicated the almost instantaneous comprehension of my error, and I took his advice so to heart that it launched an entirely new phase of my writing career, which I now refer to as my “Theater Period,” out of which came such works as The Ketchup Theorem[8] and Ali’s Wall[9], in which not a single person died.

Thirty-five years later, I still reflect on his advice—a check on my predilection for writing “deeply meaningful” melodrama and a reminder not to take myself so damn seriously. Even so, when I look back at my early, failed attempts to make “great art,” I find at their core the undeveloped intuition that death is what makes life meaningful. Even in its inverse application—a worldview in which death makes life absurd and meaningless—death is still the driving force of the paradigm. It’s the IT factor in every weltanschauung because we all have to reckon with it one way or another, and great art—the aspiration of every young, earnest writer—helps us do that, even if no character has to die.

[1] Made for interesting cheers at sporting events

[2] Influences seen in my work at this time include Nancy Drew, Hardy Boys, and Trixie Belden.

[3] and the end

[4] Boyfriend moved away

[5] About said boyfriend

[6] Name of said boyfriend

[7] A typewriter, in case you are too young to remember

[8] Conceived in geometry class

[9] A very original script in which events in Ali’s life contribute to a wall being built up around her throughout the course of the play, not at all influenced by my burgeoning obsession with Pink Floyd

Tales From the Liminal is now available as an audiobook on all your favorite platforms!